I have always liked speakers with unconventional radiation

(i.e., non-forward-radiating) patterns. The first true audiophile

loudspeaker I owned was the KLH 9 full-range electrostatic. This

was in 1972. These speakers had a "you are there" imaging

presence and boxless sound quality I had never heard before.

There were many reasons for this, but an important key to their

performance was the fact that they radiated sound both for-

ward and rearward.

To me, imaging is the real magic in a loudspeaker's performance.

All the conventional parameters of a loudspeaker's performance

(linear wide frequency response, low distortion, excellent transient

response, etc.) are important, but imaging is that elusive quality

that brings the musicians into the room or brings you into the

concert hall or into the movie. Imaging allows the suspension of

disbelief and lets you imagine that what you are listening to is

real. The KLH electrostats were wonderful in this regard.

Full-range electrostatic panels of that day, including the

KLH, however, had many shortcomings, including very high price,

large size, difficult power requirements (I used a set of Futterman

output transformer-less vacuum tube amplifiers, which did a bet-

ter job than most with problematic electrostatic speaker loads),

limited dynamic range, limited bass performance, positioning dif-

ficulties, etc. It seemed to me that it would be fantastic to create

a loudspeaker that brought the benefits of these exotic, impracti-

cal panels into a product that made sense for the majority of

listeners in the real world.

I designed my first bipolar loud-

speaker in 1973 or 1974, a narrow-

format tower incorporating multi-

ple small-diameter bass/midrange

drivers arrayed on both the front

and rear baffles along with

piezoelectric tweeters and passive

radiators. It was quite successful in

the marketplace. It also brought me

a phone call from the great loud-

speaker designer Jon Dahlquist

(who was also introducing a loud-

speaker with a piezoelectric tweet-

er—the soon-to-be-famous, time-

aligned Dahlquist DQ 10, which was

known for its "boxless" sound) and

led to a long and enjoyable friend-

ship between myself and Jon, as

well as with his partner, the

late Saul Marantz. (Marantz not

only founded the company which

still bears his name, but was the

creator of a number of classic

high end audio components; he also

recognized and helped cultivate

design talent in others—including

Jon Dahlquist and

tuner-wizard

Dick Sequerra.)

Issue 3 April 2004

Sounding Board

Definitive Technology’s Sandy Gross on Loudspeaker Design

The Case for Bipolar Loudspeakers with Built-in Subwoofers

Affordable Excellence in Home Theater, Stereo, Film and Music

hris Martens recently reviewed the Definitive Technology BP7001

SC Bipolar

SuperTower for The Absolute Sound (Issue146). During the review process, I

discussed with him at some length two of Definitive's signature technolo-

gies, specifically bipolar radiation and built-in powered subwoofers. Chris believed

these concepts would be of general interest to AVguide Monthly readers, and

asked me to write a short piece describing them (without, of course, turning the

article into a 2-page ad for my company).

“…our first product, the BP10 loudspeaker, was also a narrow

tower with basically two complete full-range driver arrays.

One faced forward and the other rearward. This is the basic

concept of a bipolar speaker. The two driver arrays radiate

sound (in phase with one another) in what is basically an

omnidirectional pattern, exactly as sound is radiated in real life

from an original sonic event."

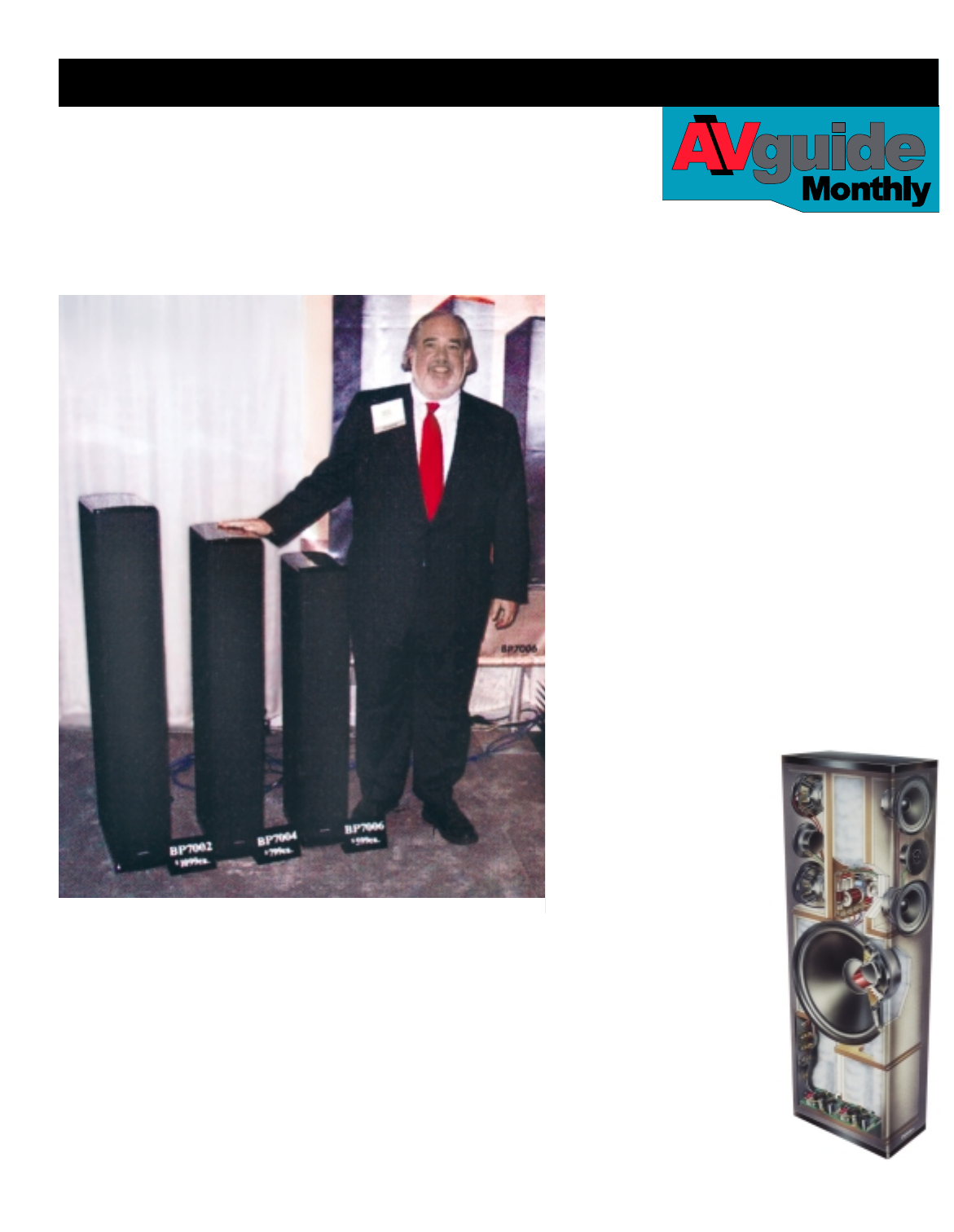

Cross Section of the

Original BP2000

Sounding Board

C